I recently watched the first episode of the documentary series called Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey. This is a follow-up to the series called Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, first broadcast in 1980 and hosted by the late Carl Sagan. I never watched the original series, mainly because I had heard that Sagan, an astronomer and astrophysicist, was also an atheist and, therefore, could have nothing of value to say about the age or origin or boundaries of the universe. (For the record, Sagan actually denied being an atheist—one who believes there is irrefutable proof for the non-existence of God—but he rejected the idea of God as a personal being.)

The new series is hosted by Neil de Grasse Tyson, who, as a young college student, was strongly influenced by Sagan to take up science as a career. Like Sagan, he became an astrophysicist, and, also like Sagan, he rejects the idea of a personal God who created and now controls the universe. For some reason, I’m not troubled by that knowledge the way I was more than thirty years ago when I learned something similar about Carl Sagan. I guess you might say my thinking has “evolved” in that regard. 🙂

Somewhere along the way I came to the awareness that “all truth is God’s truth.” So simple, yet so profound. The first time I heard that statement, I knew it was consistent with all that I believed about God and the universe. The one problem with it is how to determine what really is truth. Is it okay to believe that there are very few things about which we can be confident that we know the full, total, and complete truth? The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, as it were?

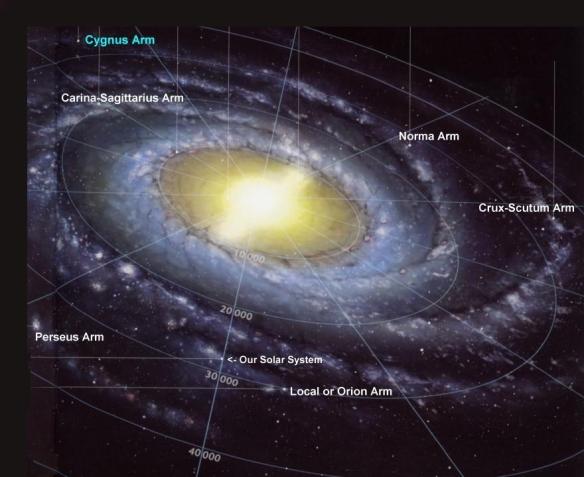

The main thing I took away from episode one of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey is a new awareness of the enormity of the universe. The photo below is an artist’s rendering of the Milky Way galaxy.

You can see the little dot that represents our sun with its planetary system. Scientists estimate there could be as many as 300 billion stars, many much larger than our sun, in the Milky Way galaxy. Each one could have its own system of orbiting planets. And here’s the almost incredible thing—there may be as many as 300 billion galaxies in the universe. As many galaxies as there are stars in the Milky Way!

I used to believe that the more we learned about this vast universe in which our entire solar system is but an infinitesimal speck, the more we would recognize the need for a Creator with power sufficient to bring it into existence. I now understand how intelligent people—like Sagan and Tyson—can look at the universe and conclude that it is all there is and that there is no need for any greater power.

Of this much I feel pretty confident today. If there is a God who made this vast universe—a personal, sapient being who knows and feels and thinks and acts—and if that God somehow took on human form, as Christians say he did, in the historical figure of Jesus, then one thing that God and the God-man are not is fully comprehensible to humans.

Everything about that God and that God’s human incarnation is substantive and meaningful. The God who brought the universe into existence, then—through some process and for some purpose—created human beings (“in his image,” if we believe the biblical narrative), then took on the form of a human in order to relate personally to those humans and do something for them that they could not do for themselves… that God does not deal in trivialities.

One summer around thirty years ago, I was sitting in a lecture hall on the grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. The venue had been arranged by the Center for Christian Study, an evangelical ministry focused on university students, as the setting for a series of presentations by Dr. John R. W. Stott (now deceased), one of the most respected voices in evangelical Christianity at the time. I still remember one particular sentence from one lecture as clearly as if I had just heard it for the first time five minutes ago. Dr. Stott said,

Most non-Christians in the west don’t reject the Christian message because they find it false. They reject it because they find it trivial.

Thirty years later, I find that statement just as jarring—and with the same ring of truth—as I did then. And yet, when non-Christians—both secular and religious or spiritual—observe the contemporary Christian community in America, I fear that they have little choice but to conclude that much of what we do and say is trivial.

Our petty rivalries and in-fighting. Our backbiting and jealousy. Our crass misuse of power and authority and resources. Our violation of the trust placed in our leaders and teachers and clergy. Our manipulation of vulnerable people for our personal gain. Our materialism and superficiality and hypocrisy.

We have created a God in our image, one that we are then able to use for our own purposes and to advance our own agendas. Instead of conforming to the will of God, we force our truncated perception of God to conform to ours. And non-Christians (along with those who once considered themselves Christians but are no longer involved in organized religion) find the whole enterprise unworthy of any reasonable concept of a creator-God. They never get a chance to consider the spiritual depths and theological complexities with which Christian scholars fill their days and their books. They can’t get past the trivialities of people who claim to be disciples of Jesus and servants of the Most High God, yet act like self-centered babies.

Much of what I saw in that first episode of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey was familiar to me from my science classes in high school and college. There was, however, one bit of information—and one important character—which I encountered for the first time. It was the story of Giordano Bruno, a 16th century monk who challenged the teaching of the Catholic church as to the origin and development of the universe.

Influenced by the theories of Nicholas Copernicus, Bruno advanced the idea—directly contradictory to church dogma—that the earth revolved around the sun and was not itself the center of the universe. As a result, he was accused of heresy, tried and found guilty, and burned at the stake on January 7, 1610. At his trial, Bruno was asked how he could promote a theory so much at odds with the teachings of the church, to which he replied: “Your God is too small.”

Over the past few years, as I have reexamined virtually every aspect of my life and my most fundamental beliefs, I have had to conclude that my idea of God was truncated and self-serving. My God was indeed too small, and I was likely contributing to the perception that Christian faith could be caught up in trivialities altogether unworthy of the God who created the universe and then stepped into it in the person of Jesus.

Some say I have abandoned the true faith and succumbed to the influence of postmodernism. I think I have matured in my faith while still maintaining a commitment to orthodoxy. I intend to share what I think is the fruit of my faith development and spiritual formation in the pages of this blog. That way you, my readers, to whom I owe a debt of gratitude, can decide for yourselves.

Soli Deo Gloria.

I am uncertain what it is that you want us, your readers, to decide for ourselves. Whether you abandoned the faith? Embraced postmodernism? Whether there really is “fruit”? Is it important for us to make decisions of such a nature–I certainly don’t have the wisdom or desire to make such judgments. But I will pray for you as you wrestle through it.

I would be eager to learn about how repentance of making God too small spiritually transforms the heart and mind and leads towards new and deeper levels of orthopraxy. I wonder if a Spirit filled orthopraxy will be impervious to the charge of triviality. How has the maturation of your faith made you less trivial than you were 5, 10, 30 years ago?

I pray that you experience the favor of God as you co-labor with the followers of Christ in the journey we call life.

I tried to make the point that much of our “praxy” is decidedly not “ortho” because our view of God is truncated, and we don’t even realize it. I listed several examples of attitudes and behaviors I consider exercises in triviality and less than worthy of the classic view of God. If the “charge of triviality” is valid, we should not want to be impervious to it. As for my personal experience, I hope I am more consistent in emphasizing the character of Jesus–the thing that really matters in our faith-walk–and less focused on doctrinal precision that can lead to a judgmental, unloving spirit. Whether or not I am successful in at least articulating that change in perspective is what I am asking my readers to judge for themselves. –E.

Absolutely profound, Eric. I have found myself in a similar place as you are after nearly 40 years in pastoral ministry. A more awesome appreciation of God and more humble about myself and my own ideas.

Thanks for the comment, Dennis. I am grateful that you read my stuff, and I always appreciate hearing from you. –E.

I USED to have a passion for astronomy. Note USED to. That passion got killed in me by the standard Christianese putdown/comeback when you make the mistake of showing your passion (like a Saganesque awe of the Cosmos) to someone:

“IT’S ALL GONNA BURN.”

Whatever you do, DON’T breathe a word of it around Christians. They won’t literally burn you for Heresy, but they’ll shun you for Apostasy and Unbelief.

I’m now Catholic BECAUSE of the RCC’s patronage of the arts and sciences. We have the Vatican Observatory and the Pontifical Academy, they have the Kentucky Creation Museum.